This week the Kirby Estate finally settled with Marvel—ending a long standing feud between the "House of ideas" and the guy who came up with them. The sum they settled on is not disclosed, but considering he had a hand in creating 12 of the top 100 grossing movies of all time—it's a safe bet it isn't enough.

In honor of Kirby's family finally getting a fraction of what's due to them, I want to publish an excerpt from my memoir "Fakebook"—the inside account of my social media hoax. In this scene, I reflect on living on the same street as my hero—and finding inspiration in his example to re-commit to my art.

Thanks Jack!

I put the phone down on my chest. I was tired, and had work in the morning, but my mind was too active for sleep. I looked ahead at my bedroom wall.

The ambient light of the building to the north come in through the curtain-less window, as the heavy base of nightclub on my east permeated through our shared wall as a low register beat. A house-music lullaby.

Balanced on the dresser that didn’t quite close was the promotional packaging I illustrated for the latest Iron Man toy line. And tacked to the wall on the left was my unfinished charcoal drawing.

I hadn’t touched it in over a year—since well before Fakebook began. The figure was still hunched over, looking sad, depressed, and unfinished. It was a statement on inaction. It’s almost finished by being unfinished, and I was losing interest in looking at it.

Meanwhile, the Iron Man box—with it’s high gloss finish—was proud. Bold. Dynamic. Complete.

It still struck me as a sort of coup. I used to draw super heroes in the margins of every notebook I ever had. All day long, in school, I’d draw these heroes. And now I got paid to do one. It was—well—neat.

And this was a Jack Kirby creation. Stan Lee is more well known, but in my mind, Jack Kirby is the truer genius. He’s the artist who co-created just about every super-hero you know—Captain America, The Hulk, The X-Men, Thor, Fantastic Four, Iron Man...you name it.

It’s amazing how prolific and enduring his legacy on popular culture is. Each one of these characters that he drew under deadline has outlived him and spawned billions of dollars and hundreds of millions of fans.

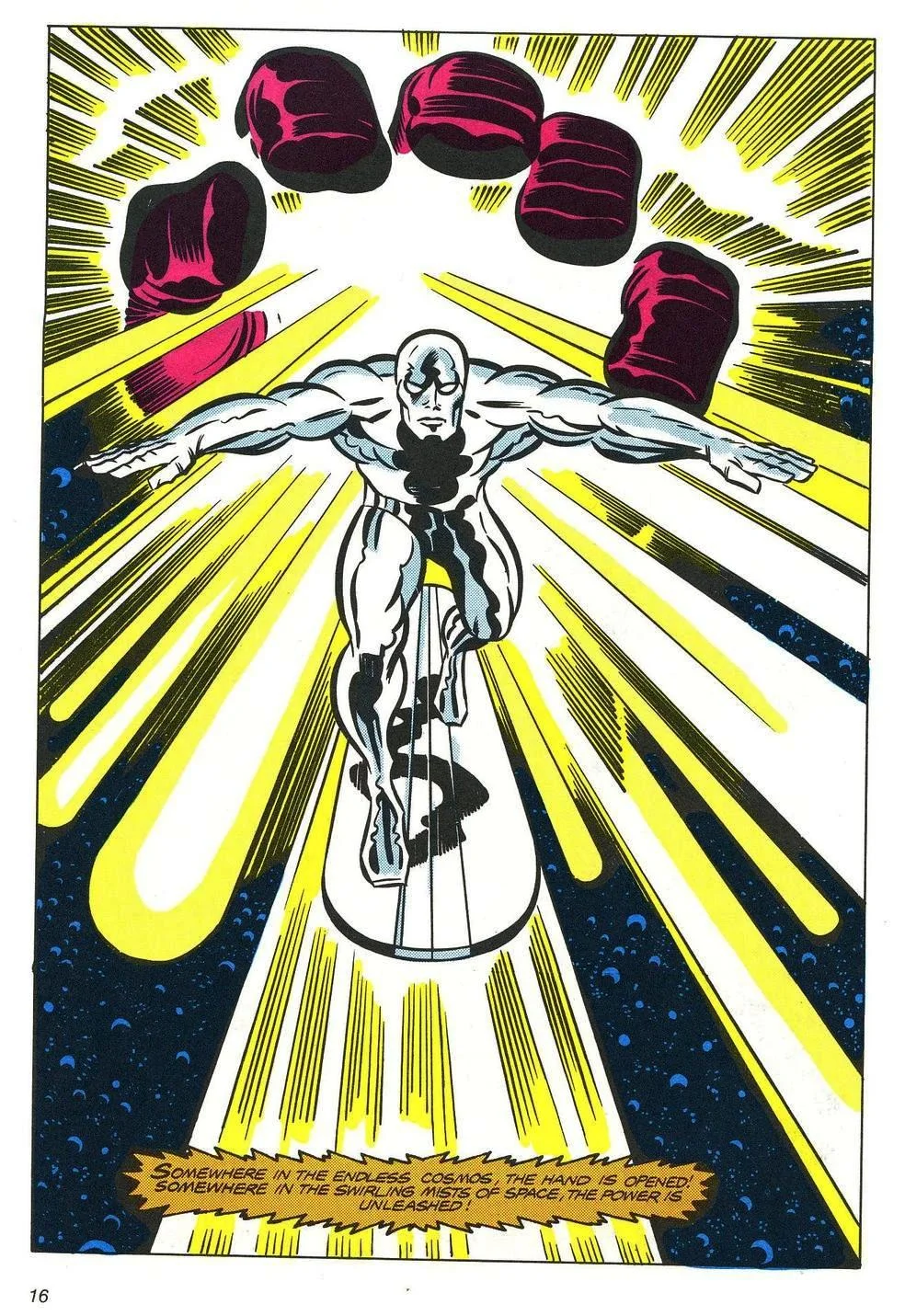

There’s a pop-art quality of his illustrations—their unapologetic grandeur and powerful dynamism. But the brilliance isn’t easily accessible—it’s out of step with modern, naturalistic, sensibilities.

I mean, his drawings mock the very notion of nuance—but there is a deep humanity to it. How else could all the crazy, ridiculous concepts he came up with manage to endure?

Take The Silver Surfer as an example.

Think about it; a surfer who is silver...what a dumb sounding idea. If the thought of a naked silver guy who rides a surfboard around outer space ever occurred to me, I’d dismiss it immediately.

Yet in Kirby’s hands, it transcends the zeitgeist of 1960’s surf mania and cold war space race it was created in, and made something that’s both timeless and so wonderfully of its time.

In his hands, a surfboard became mode of travel that was simple and elegant—all he needed to soar through the universe was a place to stand.

But despite how much his flight evokes freedom, he himself was a slave—fulfilling his side of the faustian bargain that transformed him from just a man into the Herald of Galactus, Devourer of Worlds—forever in search for new worlds to be sacrificed for the brief appeasement of his master’s appetite.

That is, until he arrived on Earth, and was forced out of the sky. Here, he walked among the people of a world whose destruction he summoned. He turned on his master, helped save Earth, and as punishment became exiled to it. He regained his soul, but it cost him the sky.

It’s so elegant and grand. A beautiful and bold tale of compromise and rediscovery wrapped up in a cosmic adventure that’s captured imaginations for 50 years and counting.

And to think—he grew up here, on Delancey Street, where I live now.

I lied on my bed—80 feet and 80 years away from where a young Jack Kirby lied on his—and looked ahead at the superhero artwork that took me almost a month to make. I looked into the eyes I drew on a face Jack Kirby imagined.

Kirby was a guy like me. He had bills to pay, he had deadlines, he had a boss. He was a guy working for a wage. He made a living, and not much more, never getting the money or credit he deserved—never making as much money as the lawyer who approved my version of his creation.

But damn it, he built a legacy out of nothing but pencil lead—a legacy of original ideas and restless creativity, and was one of the titans in defining a new art form.

So far, my legacy was a drawing unoriginal enough to please three legal departments.

I feel my phone vibrate on my chest. It’s Juror 10, responding to me teasing about court room humor. “It’s my favorite kind,” she wrote with a little winky face.

I got out of bed, walked up to the unfinished drawing next to my Iron Man illustration, and pulled it off the wall. I wasn’t interested in it’s subject matter any more, or in the hollow facade it maintained.

I saw it clearly—it was just an ornament. I hadn’t worked on it in years, but taking it down would have meant I’d given up on making real art. I no longer felt the need for its false reassurance.

I went to take down the Iron Man box from its shelf, but hesitated. I unburdened the box with the pathos of being my great finished work or this great symbol of client servitude.

I saw it as what it was—an example of craft, and a tribute to what can come out of dreaming on Delancey Street.

I still loved it as my illustration, but I knew it wasn’t my art. I was living inside my art, both online and off.

Fakebook had people laugh, and feel, and captured imaginations. It did everything I want art do. And the moments that Fakebook gave me—that intoxicating feeling of tapping into something and creating a stranger world for my audience—it was worth the agony that came with doing it.

I like art. I like making art, because it’s important. It speaks to people, shifts their perception of the world, changes what people believe to be possible—making more things possible. And I was now remembering that. And the things I like to do began to feel like an option again.

What truer tribute to Kirby could there be than to imagine something new?

And I decided then that I owed my Fakebook audience a satisfying conclusion. And I finally knew I was ready to tell it.

Dave Cicirelli is an author and artist who specializes in hoaxes as social commentary. You may have bought a Fake Banksy from him in Central Park, or you may have have seen on Facebook that he disappeared into Amish country under nefarious circumstances.

Fakebook: A True Story Based On Actual Lies recounts his six-month long social media hoax, and all the online and offline drama it created.

Publisher's weekly called it a "knock out." No big deal.